The Norman Turnbull/Grace Atkinson Archive

The Early Years, Marriage, Raising a Family, Golden Years

My Grandfather, Norman Leslie Turnbull, was a prolific writer and photographer throughout his life. I did not realize just how prolific, however, until I was handed a giant Rubbermaid tub of his poems, notes and sermons, and another tub full of photo albums at the beginning of 2016.

It had long been my goal to digitize these documents and photos so they could be shared by dozens of Norman’s relatives simultaneously, and I eagerly dived into the daunting collection. Little did I know how long it would take to complete the task.

Thus the Genesis of the archive you find before you today. As you view the items on your screen, captured just as they exist on thousands of scraps of paper, I trust you will find as many interesting insights as I have in the process of scanning these items. If you knew Norman Turnbull personally, I hope they will bring back great memories of what he was like.

- Ted Deller, March 2019

Paper Archives

Approaching the thousands of papers contained in this archive was an intimidating task. Thankfully there had been some effort made previously to organize the documents into folders and themes. For this I am grateful to all who may have touched the files in the years before I started working with them.

Methodology

Methodology

I started out simply scanning the entire contents of these manila file folders into contiguous PDF (Portable Document Format) files. However it quickly became apparent that giant PDF files with hundreds of poems, correspondence and jottings, all simply following one another sequentially as they appeared in the folder would not be of much practical use for readers. It would take a lot of scrolling to simply view the entire archive, the file sizes would be enormous, and discovering a particular poem would be left almost entirely to happenstance. Let alone the idea of re-finding a poem later.

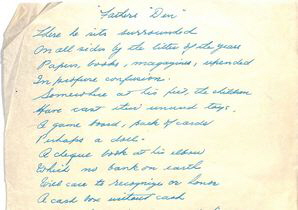

I changed my approach very early in the project, after discovering that Norman had given most of his poems and writings a title of one sort or another. As a result, each document has now been saved under its own title whenever possible. In a very few cases where a poem or sermon did not have a title, but clearly was substantial enough to warrant being saved individually, I came up with a title for it – often using the first few words of the item for ease of searching later.

By necessity there are also groups of “miscellaneous” writings and poems – often comprising incomplete poems, single pages of notes or jottings, and other partial communications.

Duplicates

Norman created several drafts of some poems, refining each one in longhand cursive before, in many cases, typing them out.

As the years went by, he would make refinements – often noting them in the margins or at the bottom. Since there was no such thing as a photocopier, if someone expressed an interest in one of his poems, he was left to either recopy it by hand or type a new copy, sometimes using carbon paper to create a duplicate.

This led to a large number of near-duplicates of items in the collection. I have chosen to scan every piece of paper in the archive, with the exception of pages which were clearly exact duplicates of items already scanned (carbon copies of poems, for example). Of the thousands of pages within the archive, only about 30 were excluded as exact duplicates or carbon copies. Everything else is copied digitally just as it was left.

As I went through the folders, I began to notice that the same poem would often crop up in several manila folders – perhaps one time as a typed copy, then several folders later as a handwritten outline or preliminary draft.

Technology allowed me to go back and append each of these drafts to what I have deduced to be the final version in most cases, keeping them together for ease of searching. As a result, you will discover upon opening many of these PDF documents that a typewritten version of the poem shows up first, followed by earlier typed or handwritten versions that were discovered in the archive.

The files are stored in a directory structure based on general groupings (for example, Poems and Writings, Sermons and Prayers, Correspondence) which should help guide you through the collection.

For more tips and hints on how to navigate the directory (tree) structure, check out the Documents section of this website.

Photographic Archives

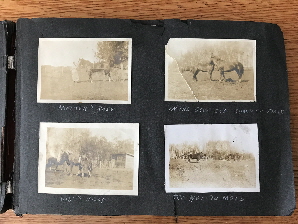

Along with the many folders of papers were more than ten photo albums. Some were large and others were relatively small – a few snaps in an Eatons card box for example. The photo archive consists of images captured by Norman Turnbull, Grace Atkinson, and at least two albums of images collected by Norman’s mother, Cecilia Turnbull.

Challenges

Challenges

In some cases, scanning the photos in these collections was easy – the images were collected loosely in a box and could be handled with care but relatively little difficulty.

There were also a number of albums that provided challenges when it came to the removal of the photos. In one case, they had been glued in place. Removal was impossible and the images had to be scanned in situ.

The “magic albums” that seem ubiquitous among family photo collections proved to be an interesting challenge as well. The photos are held in place by thin lines of adhesive, which seems to get stronger as an album ages. Either that, or the adhesive loses its grip on the images entirely and they all simply fall out. I encountered both issues in the course of dealing with the same album in one case.

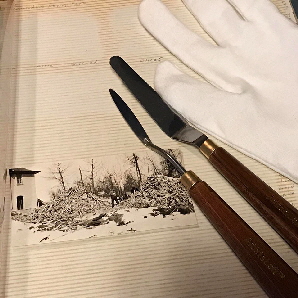

The Smithsonian website suggested using a “micro spatula” to work under the photos and release them from the page. I didn’t have a micro spatula handy, so opted for a painter’s pallet knife, which worked brilliantly. Another tip from a non-archival page suggested using a hair dryer (or in my case a heat gun kept at a distance). This did a great job of loosening up the adhesive in the most stubborn cases where nothing else would work.

Grace Atkinson was a creative woman and spent many hours assembling a number of the photo albums -- painstakingly sorting through images, removing them from older photo album and consolidating them in newer ones it appears. There is some resulting damage from that process including cropping of images to fit many onto one page. Grace was an enthusiastic cropper, and in some cases you will note very tiny images – bits and pieces with people or children in them – that have been cropped from larger shots.

A Word About Cameras

A Word About Cameras

One of the fascinating things about the black and white collection is the variety of cameras that recorded images of the Turnbull family’s life. You will notice some high-quality images along with many lower-resolution ones which I assume are from more run-of-the-mill ‘box’ cameras which were popular in the early 1900s.

Norman Turnbull was always interested in photography, and I imagine he invested in better and better camera technology as the years went on. All of this is to explain why there may be a perfectly crisp shot of someone’s wedding right alongside a number of blurry ones. Grace appears to have pulled together photos from several sources as she assembled her albums, capturing different angles of the same events in some cases.

Focus and framing were also issues in early photography. Cameras offered only rudimentary viewfinders and the lenses offered few options beyond infinity and perhaps one closer setting.

Captions

I have endeavoured to capture any captions that existed, either around the photos on the album pages or on the front or reverse sides of the photos themselves.

In cases where a caption appeared in the album, along with similar (or sometimes conflicting) information on the reverse of the photo, I have combined or used my best judgment to determine which caption is correct. In some cases you will note that both bits of information have been provided for the viewer.

Where notes are written on the backs of the photos – by the owner or a subsequent organizer – I have scanned these reverse sides, and included them in the resulting collection. The exception is a number of photos that simply had a year (“1985” for example) written on the back. This information was captured as meta-data and embedded in the photos, and while the reverse side was scanned it was not included in the final collection to save space.

Organization

Organization

For the most part, I have scanned the photos in chronological order as they appeared in each album. The image file numbers indicate from which album they originated and in which sequence.

- TA-A5-021.jpg

In this case the scan is from Album 5, image 21.

Where it seemed appropriate or helpful to the viewer, I have included an overview shot of each album page prior to displaying each image in isolation. The idea is that this allows a glimpse into the way the album organizer had hoped things would be viewed in a pre-digital world. In some cases the series of overview images appears at the end of the image gallery.

In cases where the overview photo appears adjacent to the individual scans I have tried to sequence the photos from the top left, moving clockwise around the page. There are, however, instances in which several photos were obviously grouped together vertically (families, or events) and in these cases I have prioritized these groupings over the clockwise sequence.

In one or two of the plastic sleeve-style albums it seemed obvious that some photos of the same day’s events (a family gathering, for example) had been grouped in one spot, then other photo stragglers from the same day had been added many pages later simply because some time had gone by, and other photos had been added to the album in the intervening time. Grouping the newly-found images with the first photos from the event would have involved rearranging many intervening pages, so they got out of sequence. The joy of digital photo sorting meant that I could easily re-group these photo stragglers, and in instances where it seemed appropriate I have done so.

In the case of plastic sleeve albums, there was little opportunity for artistic layout. There were simply four spots on each page and the photos were inserted accordingly. These images were scanned sequentially as described above, and then the overview images were appended en masse to the end of the catalogue.